In 1946 Peter Drucker argued that the corporation had become the defining institution of modern life. Two decades ago The Economist called the company “the most important institution of our day.” Tracing the corporation’s history helps explain how its meaning and power have shifted — from material force to immaterial leverage — and why both forms now coexist and compete.

Material beginnings

The modern corporation emerged in 17th-century Holland with features that survive today: permanent share capital, tradable shares, separation of ownership and management, limited liability and state charters. England adopted and expanded these ideas after the Glorious Revolution. France, by contrast, kept more state-controlled capital, partly because of early private failures such as John Law’s ventures.

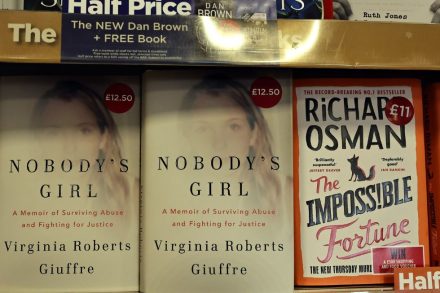

Dutch and English joint-stock companies, however, served state aims. With royal charters they were instruments of mercantilist and imperial policy. They ran wars, administered territories and enjoyed monopolies backed by state power. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) — the first major global corporation — fielded some 150 ships, 40 large warships, 50,000 employees and a private army of 10,000. The English and French East India companies matched that scale later, contending for colonies, resources and routes.

England ultimately triumphed. By Plassey in 1757, the British East India Company (EIC) under Robert Clive had seized vast swathes of India; for a century the EIC effectively governed large territories on Britain’s behalf. In southern Africa the British South Africa Company, led by Cecil Rhodes, raised private forces, levied taxes, ran courts and allocated land by royal charter. These corporations were materially manifest: fleets, guns, soldiers, territory and the capacity to wage war. They were, in essence, private arms of empire.

Immateriality and globalization

A century later the corporate form changed radically. From the late 20th century into the early 21st, corporations shed many physical burdens and became increasingly “immaterial.” Globalization fragmented production: assembly lines were broken into specialized pieces scattered across many countries. Firms focused on core competencies, outsourcing manufacturing, services and even research to wherever labor and skills were cheapest or most efficient.

The large corporation retained brands, patents and managerial controls while outsourcing production and many staff obligations. In this model, value lives largely in intangibles — intellectual property, networks, reputation and data — rather than in ships, barracks or mines. Thomas L. Friedman’s image of a “flat” world captured how design, finance and services could be distributed globally, allowing large firms to be relatively “bodyless” while coordinating dispersed suppliers and contractors.

Resurgence of materiality

Recent shocks have checked globalization’s momentum and revived corporate materiality. Geopolitical rivalry, pandemic-related supply-chain breakdowns, automation that raises developed-country cost-competitiveness, and protectionist industrial policies (notably in the U.S.) have made firms rethink extreme outsourcing. Vertical integration, onshoring and reinvestment in physical capacity have reappeared as strategic priorities. In several industries, having control over tangible assets — factories, inventories, secure supply links — has regained importance for resilience as well as for national security.

AI and a new kind of power

Yet at the same time a different trajectory of immaterial power is accelerating: artificial intelligence. AI’s core assets are soft — data, algorithms, compute — and highly scalable. These technologies can multiply economic and political impact without a proportionate increase in people or physical capital. Startups and research labs with small, highly skilled teams can generate outsized effects because models and software scale cheaply once trained and deployed.

OpenAI’s November 2023 crisis dramatized this new logic: when its board dismissed Sam Altman, some 70% of staff threatened to quit; 738 out of 770 employees demanded his return and the board’s removal. The episode underscored how a company reshaping economies and institutions could still operate with a modest headcount. By 2025 OpenAI had grown to about 3,000 employees. Other major AI firms remain lean by historical corporate standards: Anthropic (valuation around $61.5 billion) had roughly 1,097 employees; Mistral AI around 150; Thinking Machines Lab about 50. Small teams, leveraged by models and cloud infrastructure, produce vast outputs.

Implications and trade-offs

These developments suggest two coexisting logics of corporate power. One is renewed materiality: states and companies rebuilding industrial bases, owning assets, and securing supply chains. The other is intensified immateriality: software, algorithms and data enabling exponential scale and influence with relatively few people or factories. Both shapes of power have geopolitical consequences. Material assets remain crucial where control of territory, resources and logistics matter. Immaterial assets reshape information ecosystems, markets and social organisation, often faster than governance can adapt.

There is a human dimension. The immaterial economy’s scalability threatens many jobs as AI performs tasks across blue- and white-collar work. The social cost of an immaterial-led future could be high unless policies and institutions adapt to manage displacement and concentration of influence.

Conclusion

From the VOC’s fleets and private armies to today’s AI labs housed in small offices but serving global platforms, corporations have shifted from manifest material force to forms of immaterial leverage — and now both forms reassert themselves. Understanding how and where firms invest — in factories or in models, in ships or in servers — will be central to grasping power in the decades ahead. The contrast between brute, territorial power and the ethereal but scalable influence of algorithms frames a defining choice for business, policy and society.