Republican efforts to use aggressive gerrymandering and voter suppression to preserve congressional power risk backfiring. The strategy depends on precise arithmetic about where voters live and how they will behave; push those calculations too far, and a wave election or changing turnout patterns could convert many supposedly “safe” GOP seats into vulnerable ones, producing large losses that reshape American politics.

Gerrymandering’s goal is simple: draw districts so that as many seats as possible have reliable Republican majorities while concentrating Democratic voters into a few districts. The technique of “packing and cracking” packs likely Democratic voters into a small number of districts and disperses likely Republican voters to build slim but widespread GOP majorities. The maps are drawn from census data and recent voting behavior, and their effectiveness rests on voter behavior remaining stable from one cycle to the next.

But stability can break. First-past-the-post systems magnify small swings in votes into large swings in seats, as recent UK elections illustrated: modest changes in vote share produced dramatic seat turnovers. In the U.S., extreme gerrymanders thinly spread presumed Republican voters across many districts, increasing reliance on low Democratic turnout and on past voting patterns holding steady. If voters change their behavior — because of national events, candidate unpopularity, demographic shifts or higher turnout in targeted groups — the levee can be overtopped. A wave election can convert many narrow GOP margins into Democratic pickups.

Several specific risks make the Republican strategy fragile. The data used to draw districts can be stale. Maps based on 2010 or even 2020 patterns may not reflect rapid demographic shifts in fast-growing states. Assumptions about groups such as Hispanic voters can be particularly perilous: gains some Republicans saw among Hispanic voters in 2024 could prove temporary or reverse as parties’ messages and actions change. In places like Texas, where Republicans have banked on Hispanic voting patterns and low turnout, higher-than-expected turnout or changes in partisan alignment could turn supposed gains into losses.

Donald Trump’s influence compounds the problem. Where incumbents historically constrained excessive gerrymandering—because making districts too marginal puts their own seats at risk—Trump’s pressure and threat of primary challengers have silenced such internal resistance. That dynamic can push state parties and mapmakers to chase short-term political goals rather than prudent math, producing maps that maximize seats in the near term but leave many seats precarious in a different national environment.

When gerrymandering is pushed to extremes, the other GOP answer is voter suppression. Suppression strategies create logistical and bureaucratic obstacles—strict ID rules, registration hurdles, purges of voter rolls, restrictions on mail ballots, and reduced polling access—that can depress turnout among groups more likely to vote Democratic. But voter suppression has limits. It can be administratively difficult to implement uniformly across many jurisdictions, legally contested, and politically risky. It also often hits the very Republican constituencies the party relies on—older, lower-income, less-educated voters who may struggle with new barriers. And crude suppression can transform voting into an act of defiance and mobilize those targeted.

Additionally, most election administration in the U.S. is run by states and localities, not by a federal apparatus easily repurposed for nationwide suppression. Even with current GOP control of many state governments, loss of state legislatures in a wave election would curb the ability to entrench suppression measures for future cycles. Creating a federal-level infrastructure for suppression would be legal and political minefields, and in many cases the practical mechanisms—postal voting bans or deploying federal agents to intimidate voters—would likely provoke backlash and legal challenges while being ineffective at producing the imagined fraud suppression.

Suppression tactics that rely on intimidation—deploying ICE or other federal agents to polling places—depend on myths such as widespread noncitizen voting and are more likely to spur anger among Latino, Black and other communities than to prevent votes. Agencies like the military, the National Guard or the FBI are unlikely to be used systematically for partisan voter intimidation without severe legal and institutional consequences.

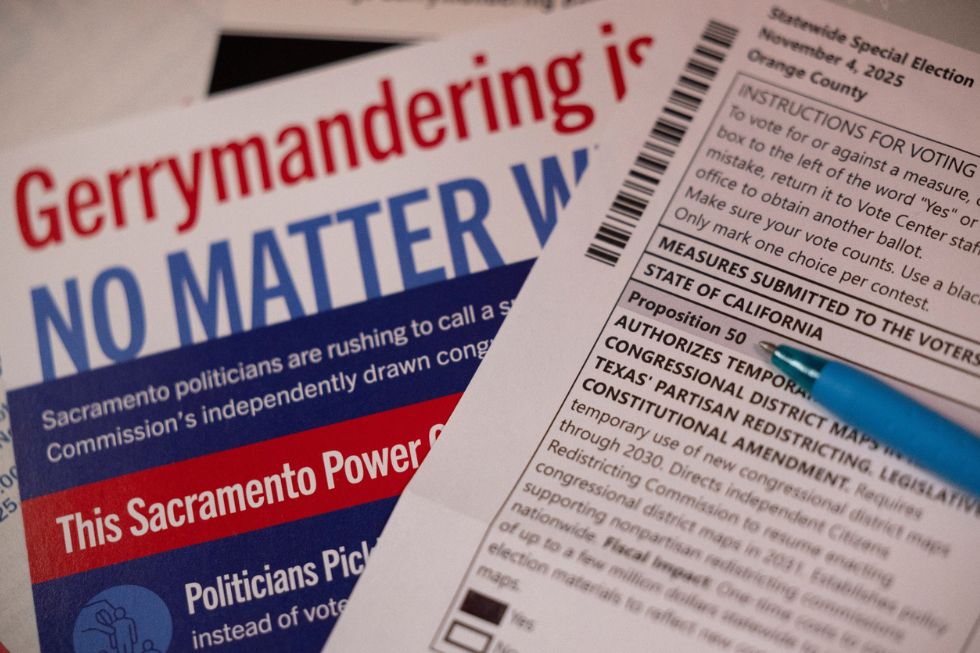

There is also a reputational and political risk. High-profile, clumsy moves at gerrymandering or obvious efforts at disenfranchisement can alienate independents and moderate voters. Voter anger at perceived unfairness can produce strong backlash at the ballot box. The recent California response to an aggressive redistricting move in Texas—where a “Proposition 50” style retaliation redrew maps and won near-universal voter backlash in opinion polls yet secured strong approval at the ballot—illustrates how voters may respond to what they see as overreach.

In short, the arithmetic of extreme gerrymandering plus suppression is fragile. It rests on assumptions about demographic behavior, turnout, and legal and administrative feasibility that can be overturned by electoral waves, shifts in group preferences, or backlash against heavy-handed tactics. Overreach can both weaken incumbent protections and inflame the very constituencies that would oppose those measures, producing more damage than gain.

If Republicans cannot execute suppression reliably and without provoking countervailing mobilization, extreme gerrymandering could result in more vulnerable seats than gained ones. The combined strategy risks converting short-term advantages into long-term instability for GOP majorities. The most effective safeguard against that outcome may be the same thing that has always constrained excessive partisan mapping: the self-interest of incumbents who prefer secure seats, the rule of law, and electoral backlash when tactics are seen as unfair.

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece.]

The views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.