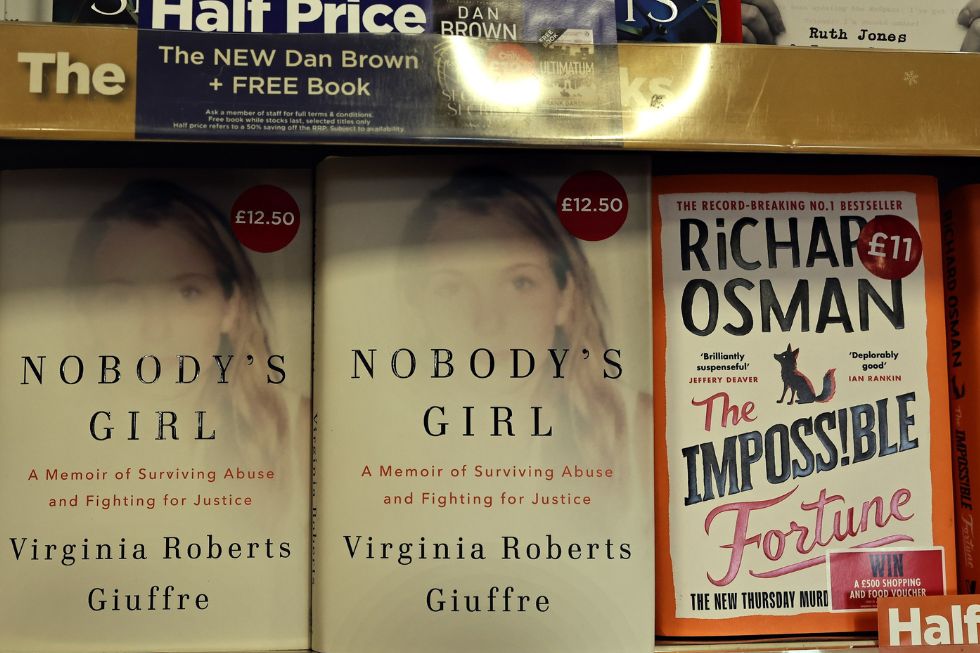

Virginia Roberts Giuffre, one of Jeffrey Epstein’s most prominent accusers, recounts in her posthumous memoir Nobody’s Girl a life shaped by trafficking, abuse and a long legal fight to be believed. Born in Sacramento in 1983 and raised in Palm Beach County, she started at 16 as a towel girl in the Mar-a-Lago spa, a job her father helped secure. There she was approached by Ghislaine Maxwell, who later introduced her to Jeffrey Epstein; Giuffre says that encounter set in motion a pattern of grooming, travel and exploitation that defined much of her youth.

Nobody’s Girl follows a broadly chronological arc interrupted by flashforwards, beginning with a memory of a teenage Virginia at the Louvre. Epstein, who had taken her overseas, describes a tapestry to her — an early, surreal marker of how she was moved into circles she had never imagined. Years later she returns to Paris to testify against Jean-Luc Brunel, an associate of Epstein’s, underscoring the book’s framing as a kind of hero’s journey from victimhood to testimony.

Giuffre’s account highlights how abusers often cloak themselves in prestige. She describes being trafficked to academics “from prestigious universities” and recalls Maxwell presenting Epstein as a “genius.” Those claims fit broader reporting that Epstein misrepresented academic credentials to gain influence — a pattern that helped him move from schoolteacher to finance and into wealthy networks that facilitated his abuse.

The memoir is shadowed by Giuffre’s death by suicide in April 2025, at 41. Her death underscores the long-term toll of trauma and the burden borne by survivors who must repeatedly prove their credibility. Confronting powerful figures — Epstein (deceased), Maxwell (convicted and imprisoned), and public figures who associated with them — exacted an emotional cost. Giuffre’s death amplifies the broader public discussion about believing survivors and the psychological consequences when institutions and elites deny or minimize allegations.

Nobody’s Girl also lives in the context of #MeToo, which helped shift public attention to sexual violence and its institutional roots. The movement’s surge in 2017 contributed to broader awareness of exploitation by powerful men and the systems that protect them. In Giuffre’s case, the involvement of a royal — Prince Andrew — magnified media interest. Giuffre’s evidence included a photograph of Andrew with her when she was 17, and her later civil suit produced a settlement and a statement from the then-duke acknowledging her as a victim. For Giuffre, the settlement represented a measure of vindication and compensation for the practical costs of trauma, from therapy to lost earnings — a defense against the common assumption that financial settlements undermine credibility.

Public scrutiny and new records have kept the case alive. Flight logs, formerly obscure, proved pivotal: they corroborated victims’ accounts of travel with Epstein and Maxwell and supplied a paper trail linking minors to wealthy passengers. Testimony from pilots, drivers and staff — detailing the constant arrival and departure of young women and Maxwell’s role in directing them — helped investigators assemble a pattern of grooming that individual stories alone might have failed to convey. The abundance of consistent detail across multiple accounts created the evidentiary weight that eventually produced legal consequences.

Giuffre, in the memoir and interviews, stresses that the abuses she endured did not occur in isolation. They required the participation, silence or willful ignorance of many people — bystanders, staff, facilitators and social connections who benefited from or tolerated the arrangement. This complicity is central to understanding how organized exploitation functions: it is a social apparatus that relies on cultural taboos about sex, institutional deference to privilege, and the incentives that keep witnesses quiet.

The unraveling of truth around Epstein and his circle also exposed the limits of public explanations offered by the powerful. Prince Andrew’s televised denials and evasions, and subsequent revelations showing continued contact with Epstein, illustrated how image-management can fail when documentary evidence accumulates. Similarly, reporting and recent releases from police files and congressional inquiries have periodically introduced new names and details — a drip of disclosures that reshapes public understanding but does not substitute for thorough investigations.

Giuffre’s book, published months after her death, arrives amid renewed releases of Epstein-related records. Some emails and documents released by congressional or investigative bodies have generated headlines implicating other prominent figures; others contradict or complicate individual accounts. As the memoir itself notes, isolated documents are rarely definitive: a full picture requires comprehensive release of files and rigorous prosecution where warranted. Giuffre maintains that speaking the truth — and securing corroboration from lawyers, experts, prosecutors and other victims — is essential to transforming testimony into actionable justice.

The memoir also critiques elitist assumptions that sexual abuse is incompatible with education or status. Maxwell’s defense at trial famously asked why an “Oxford-educated” woman would engage in such conduct — a rhetorical move that relied on the false premise that class or schooling immunizes against criminality. Giuffre’s narrative and the trial record, by contrast, show how status can be a tool that obscures wrongdoing and shields perpetrators.

There is a symbolic dimension to the book’s timing. Giuffre dedicated Nobody’s Girl to “anyone who has suffered sexual abuse,” and public responses — including the removal of royal honors from Prince Andrew — have offered some measure of institutional reckoning. Yet the book and the events around it also highlight unfinished business: criminal accountability for some, ongoing civil remedies for others, and a continuing demand for transparency from institutions that once protected the powerful.

Ultimately, the memoir argues for collective defense of truth. Giuffre’s experiences underscore that individual testimony gains force when backed by documents, corroboration and institutional persistence. The flight logs, witness accounts, staff testimonies and the accumulation of similar stories created the evidentiary basis that public opinion and some legal actors could not easily ignore. Still, the memoir warns, speaking alone is rarely enough: the truth must be defended by lawyers, investigators and a public willing to confront uncomfortable facts about power, complicity and the social structures that enable abuse.

Nobody’s Girl is therefore both personal testimony and an appeal: to recognize the cost of disclosing abuse, to resist victim-blaming, and to insist that institutions and elites be held accountable. The book arrives at a moment of renewed scrutiny into Epstein’s network, and its publication — even as it follows the tragedy of Giuffre’s death — amplifies ongoing debates about justice, credibility and how societies protect the vulnerable.

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece.]

The views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.